来源:http://www.brendangregg.com/perf.html

These are some examples of using the perf Linux profiler, which has also been called Performance Counters for Linux (PCL), Linux perf events (LPE), or perf_events. Like Vince Weaver, I’ll call it perf_events so that you can search on that term later. Searching for just “perf” finds sites on the police, petroleum, weed control, and a T-shirt. This is not an official perf page, for either perf_events or the T-shirt.

perf_events is an event-oriented observability tool, which can help you solve advanced performance and troubleshooting functions. Questions that can be answered include:

- Why is the kernel on-CPU so much? What code-paths?

- Which code-paths are causing CPU level 2 cache misses?

- Are the CPUs stalled on memory I/O?

- Which code-paths are allocating memory, and how much?

- What is triggering TCP retransmits?

- Is a certain kernel function being called, and how often?

- What reasons are threads leaving the CPU?

perf_events is part of the Linux kernel, under tools/perf. While it uses many Linux tracing features, some are not yet exposed via the perf command, and need to be used via the ftrace interface instead. My perf-tools collection (github) uses both perf_events and ftrace as needed.

This page includes my examples of perf_events. A table of contents:

Key sections to start with are: Events, One-Liners, Presentations, Prerequisites, CPU statistics, Timed Profiling, and Flame Graphs. Also see my Posts about perf_events, and Links for the main (official) perf_events page, awesome tutorial, and other links. The next sections introduce perf_events further, starting with a screenshot, one-liners, and then background.

This page is under construction, and there’s a lot more to perf_events that I’d like to add. Hopefully this is useful so far.

1. Screenshot

Starting with a screenshot, here’s perf version 3.9.3 tracing disk I/O:

# <b>perf record -e block:block_rq_issue -ag</b>

^C

# <b>ls -l perf.data</b>

-rw------- 1 root root 3458162 Jan 26 03:03 perf.data

# <b>perf report</b>

[...]

# Samples: 2K of event 'block:block_rq_issue'

# Event count (approx.): 2216

#

# Overhead Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ............ ................. ....................

#

32.13% dd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] blk_peek_request

|

--- blk_peek_request

virtblk_request

__blk_run_queue

|

|--98.31%-- queue_unplugged

| blk_flush_plug_list

| |

| |--91.00%-- blk_queue_bio

| | generic_make_request

| | submit_bio

| | ext4_io_submit

| | |

| | |--58.71%-- ext4_bio_write_page

| | | mpage_da_submit_io

| | | mpage_da_map_and_submit

| | | write_cache_pages_da

| | | ext4_da_writepages

| | | do_writepages

| | | __filemap_fdatawrite_range

| | | filemap_flush

| | | ext4_alloc_da_blocks

| | | ext4_release_file

| | | __fput

| | | ____fput

| | | task_work_run

| | | do_notify_resume

| | | int_signal

| | | close

| | | 0x0

| | |

| | --41.29%-- mpage_da_submit_io

[...]

A perf record command was used to trace the block:block_rq_issue probe, which fires when a block device I/O request is issued (disk I/O). Options included -a to trace all CPUs, and -g to capture call graphs (stack traces). Trace data is written to a perf.data file, and tracing ended when Ctrl-C was hit. A summary of the perf.data file was printed using perf report, which builds a tree from the stack traces, coalescing common paths, and showing percentages for each path.

The perf report output shows that 2,216 events were traced (disk I/O), 32% of which from a dd command. These were issued by the kernel function blk_peek_request(), and walking down the stacks, about half of these 32% were from the close() system call.

2. One-Liners

Some useful one-liners I’ve gathered or written:

Listing Events

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Listing all currently known events:</span> perf list <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Listing sched tracepoints:</span> perf list 'sched:*'

Counting Events

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># CPU counter statistics for the specified command:</span> perf stat <i>command</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Detailed CPU counter statistics (includes extras) for the specified command:</span> perf stat -d <i>command</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># CPU counter statistics for the specified PID, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf stat -p <i>PID</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># CPU counter statistics for the entire system, for 5 seconds:</span> perf stat -a sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Various basic CPU statistics, system wide, for 10 seconds:</span> perf stat -e cycles,instructions,cache-references,cache-misses,bus-cycles -a sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Various CPU level 1 data cache statistics for the specified command:</span> perf stat -e L1-dcache-loads,L1-dcache-load-misses,L1-dcache-stores <i>command</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Various CPU data TLB statistics for the specified command:</span> perf stat -e dTLB-loads,dTLB-load-misses,dTLB-prefetch-misses <i>command</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Various CPU last level cache statistics for the specified command:</span> perf stat -e LLC-loads,LLC-load-misses,LLC-stores,LLC-prefetches <i>command</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Using raw PMC counters, eg, unhalted core cycles:</span> perf stat -e r003c -a sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># PMCs: cycles and frontend stalls via raw specification:</span> perf stat -e cycles -e cpu/event=0x0e,umask=0x01,inv,cmask=0x01/ -a sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count system calls for the specified PID, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf stat -e 'syscalls:sys_enter_*' -p <i>PID</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count system calls for the entire system, for 5 seconds:</span> perf stat -e 'syscalls:sys_enter_*' -a sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count scheduler events for the specified PID, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf stat -e 'sched:*' -p <i>PID</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count scheduler events for the specified PID, for 10 seconds:</span> perf stat -e 'sched:*' -p <i>PID</i> sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count ext4 events for the entire system, for 10 seconds:</span> perf stat -e 'ext4:*' -a sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count block device I/O events for the entire system, for 10 seconds:</span> perf stat -e 'block:*' -a sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Count all vmscan events, printing a report every second:</span> perf stat -e 'vmscan:*' -a -I 1000 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show system calls by process, refreshing every 2 seconds:</span> perf top -e raw_syscalls:sys_enter -ns comm <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show sent network packets by on-CPU process, rolling output (no clear):</span> stdbuf -oL perf top -e net:net_dev_xmit -ns comm | strings

Profiling

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample on-CPU functions for the specified command, at 99 Hertz:</span> perf record -F 99 <i>command</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample on-CPU functions for the specified PID, at 99 Hertz, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -F 99 -p <i>PID</i> <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample on-CPU functions for the specified PID, at 99 Hertz, for 10 seconds:</span> perf record -F 99 -p <i>PID</i> sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces (via frame pointers) for the specified PID, at 99 Hertz, for 10 seconds:</span> perf record -F 99 -p <i>PID</i> -g -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces for the PID, using dwarf (dbg info) to unwind stacks, at 99 Hertz, for 10 seconds:</span> perf record -F 99 -p <i>PID</i> --call-graph dwarf sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces for the entire system, at 99 Hertz, for 10 seconds (< Linux 4.11):</span> perf record -F 99 -ag -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces for the entire system, at 99 Hertz, for 10 seconds (>= Linux 4.11):</span> perf record -F 99 -g -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># If the previous command didn't work, try forcing perf to use the cpu-clock event:</span> perf record -F 99 -e cpu-clock -ag -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces for the entire system, with dwarf stacks, at 99 Hertz, for 10 seconds:</span> perf record -F 99 -a --call-graph dwarf sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces for the entire system, using last branch record for stacks, ... (>= Linux 4.?):</span> perf record -F 99 -a --call-graph lbr sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces, once every 10,000 Level 1 data cache misses, for 5 seconds:</span> perf record -e L1-dcache-load-misses -c 10000 -ag -- sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPU stack traces, once every 100 last level cache misses, for 5 seconds:</span> perf record -e LLC-load-misses -c 100 -ag -- sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample on-CPU kernel instructions, for 5 seconds:</span> perf record -e cycles:k -a -- sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample on-CPU user instructions, for 5 seconds:</span> perf record -e cycles:u -a -- sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample on-CPU user instructions precisely (using PEBS), for 5 seconds:</span> perf record -e cycles:up -a -- sleep 5 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Perform branch tracing (needs HW support), for 1 second:</span> perf record -b -a sleep 1 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPUs at 49 Hertz, and show top addresses and symbols, live (no perf.data file):</span> perf top -F 49 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample CPUs at 49 Hertz, and show top process names and segments, live:</span> perf top -F 49 -ns comm,dso

Static Tracing

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace new processes, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e sched:sched_process_exec -a <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all context-switches, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e context-switches -a <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace context-switches via sched tracepoint, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e sched:sched_switch -a <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all context-switches with stack traces, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e context-switches -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all context-switches with stack traces, for 10 seconds:</span> perf record -e context-switches -ag -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all CS, stack traces, and with timestamps (< Linux 3.17, -T now default):</span> perf record -e context-switches -ag -T <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace CPU migrations, for 10 seconds:</span> perf record -e migrations -a -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all connect()s with stack traces (outbound connections), until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e syscalls:sys_enter_connect -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all accepts()s with stack traces (inbound connections), until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e syscalls:sys_enter_accept* -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all block device (disk I/O) requests with stack traces, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e block:block_rq_insert -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all block device issues and completions (has timestamps), until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e block:block_rq_issue -e block:block_rq_complete -a <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all block completions, of size at least 100 Kbytes, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e block:block_rq_complete --filter 'nr_sector > 200' <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all block completions, synchronous writes only, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e block:block_rq_complete --filter 'rwbs == "WS"' <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all block completions, all types of writes, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e block:block_rq_complete --filter 'rwbs ~ "*W*"' <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all minor faults (RSS growth) with stack traces, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e minor-faults -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all page faults with stack traces, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e page-faults -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace all ext4 calls, and write to a non-ext4 location, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e 'ext4:*' -o /tmp/perf.data -a <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace kswapd wakeup events, until Ctrl-C:</span> perf record -e vmscan:mm_vmscan_wakeup_kswapd -ag <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add Node.js USDT probes (Linux 4.10+):</span> perf buildid-cache --add `which node` <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace the node http__server__request USDT event (Linux 4.10+):</span> perf record -e sdt_node:http__server__request -a

Dynamic Tracing

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for the kernel tcp_sendmsg() function entry ("--add" is optional):</span>

perf probe --add tcp_sendmsg

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Remove the tcp_sendmsg() tracepoint (or use "--del"):</span>

perf probe -d tcp_sendmsg

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for the kernel tcp_sendmsg() function return:</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg%return'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show available variables for the kernel tcp_sendmsg() function (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe -V tcp_sendmsg

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show available variables for the kernel tcp_sendmsg() function, plus external vars (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe -V tcp_sendmsg --externs

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show available line probes for tcp_sendmsg() (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe -L tcp_sendmsg

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show available variables for tcp_sendmsg() at line number 81 (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe -V tcp_sendmsg:81

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for tcp_sendmsg(), with three entry argument registers (platform specific):</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg %ax %dx %cx'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for tcp_sendmsg(), with an alias ("bytes") for the %cx register (platform specific):</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg bytes=%cx'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace previously created probe when the bytes (alias) variable is greater than 100:</span>

perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg --filter 'bytes > 100'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for tcp_sendmsg() return, and capture the return value:</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg%return $retval'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for tcp_sendmsg(), and "size" entry argument (reliable, but needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg size'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for tcp_sendmsg(), with size and socket state (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg size sk->__sk_common.skc_state'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Tell me how on Earth you would do this, but don't actually do it (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe -nv 'tcp_sendmsg size sk->__sk_common.skc_state'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Trace previous probe when size is non-zero, and state is not TCP_ESTABLISHED(1) (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg --filter 'size > 0 && skc_state != 1' -a

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for tcp_sendmsg() line 81 with local variable seglen (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe 'tcp_sendmsg:81 seglen'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for do_sys_open() with the filename as a string (needs debuginfo):</span>

perf probe 'do_sys_open filename:string'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for myfunc() return, and include the retval as a string:</span>

perf probe 'myfunc%return +0($retval):string'

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for the user-level malloc() function from libc:</span>

perf probe -x /lib64/libc.so.6 malloc

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Add a tracepoint for this user-level static probe (USDT, aka SDT event):</span>

perf probe -x /usr/lib64/libpthread-2.24.so %sdt_libpthread:mutex_entry

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># List currently available dynamic probes:</span>

perf probe -l

Mixed

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample stacks at 99 Hertz, and, context switches:</span> perf record -F99 -e cpu-clock -e cs -a -g <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Sample stacks to 2 levels deep, and, context switch stacks to 5 levels (needs 4.8):</span> perf record -F99 -e cpu-clock/max-stack=2/ -e cs/max-stack=5/ -a -g

Special

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Record cacheline events (Linux 4.10+):</span> perf c2c record -a -- sleep 10 <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Report cacheline events from previous recording (Linux 4.10+):</span> perf c2c report

Reporting

<span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show perf.data in an ncurses browser (TUI) if possible:</span> perf report <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show perf.data with a column for sample count:</span> perf report -n <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Show perf.data as a text report, with data coalesced and percentages:</span> perf report --stdio <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Report, with stacks in folded format: one line per stack (needs 4.4):</span> perf report --stdio -n -g folded <span style="color: #4040f0;"># List all events from perf.data:</span> perf script <span style="color: #4040f0;"># List all perf.data events, with data header (newer kernels; was previously default):</span> perf script --header <span style="color: #4040f0;"># List all perf.data events, with customized fields (< Linux 4.1):</span> perf script -f time,event,trace <span style="color: #4040f0;"># List all perf.data events, with customized fields (>= Linux 4.1):</span> perf script -F time,event,trace <span style="color: #4040f0;"># List all perf.data events, with my recommended fields (needs record -a; newer kernels):</span> perf script --header -F comm,pid,tid,cpu,time,event,ip,sym,dso <span style="color: #4040f0;"># List all perf.data events, with my recommended fields (needs record -a; older kernels):</span> perf script -f comm,pid,tid,cpu,time,event,ip,sym,dso <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Dump raw contents from perf.data as hex (for debugging):</span> perf script -D <span style="color: #4040f0;"># Disassemble and annotate instructions with percentages (needs some debuginfo):</span> perf annotate --stdio

These one-liners serve to illustrate the capabilities of perf_events, and can also be used a bite-sized tutorial: learn perf_events one line at a time. You can also print these out as a perf_events cheatsheet.

3. Presentations

SCALE13x (2015)

At the Southern California Linux Expo (SCALE 13x), I gave a talk on Linux Profiling at Netflix using perf_events (aka “perf”), covering CPU profiling and a tour of other features. This talk includes a crash course on perf_events that you may find useful, plus it covers gotchas such as fixing stack traces and symbols when profiling Java and Node.js.

A video of the talk is on youtube, and the slides are on slideshare.

In a post about this talk, I included the interactive CPU flame graph SVG I was demonstrating.

4. Background

The following sections provide some background for understanding perf_events and how to use it. I’ll describe the prerequisites, audience, usage, events, and tracepoints.

4.1. Prerequisites

The perf tool is in the linux-tools-common package. Start by adding that, then running “perf” to see if you get the USAGE message. It may tell you to install another related package (linux-tools-kernelversion).

You can also build and add perf from the Linux kernel source. See the Building section.

To get the most out perf, you’ll want symbols and stack traces. These may work by default in your Linux distribution, or they may require the addition of packages, or recompilation of the kernel with additional config options.

4.2. Symbols

perf_events, like other debug tools, needs symbol information (symbols). These are used to translate memory addresses into function and variable names, so that they can be read by us humans. Without symbols, you’ll see hexadecimal numbers representing the memory addresses profiled.

The following perf report output shows stack traces, however, only hexadecimal numbers can be seen:

57.14% sshd libc-2.15.so [.] connect

|

--- connect

|

|--25.00%-- 0x7ff3c1cddf29

|

|--25.00%-- 0x7ff3bfe82761

| 0x7ff3bfe82b7c

|

|--25.00%-- 0x7ff3bfe82dfc

--25.00%-- [...]

If the software was added by packages, you may find debug packages (often “-dbgsym”) which provide the symbols. Sometimes perf report will tell you to install these, eg: “no symbols found in /bin/dd, maybe install a debug package?”.

Here’s the same perf report output seen earlier, after adding openssh-server-dbgsym and libc6-dbgsym (this is on ubuntu 12.04):

57.14% sshd libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

|

--- __GI___connect_internal

|

|--25.00%-- add_one_listen_addr.isra.0

|

|--25.00%-- __nscd_get_mapping

| __nscd_get_map_ref

|

|--25.00%-- __nscd_open_socket

--25.00%-- [...]

I find it useful to add both libc6-dbgsym and coreutils-dbgsym, to provide some symbol coverage of user-level OS codepaths.

Another way to get symbols is to compile the software yourself. For example, I just compiled node (Node.js):

# file node-v0.10.28/out/Release/node node-v0.10.28/out/Release/node: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, ... <b>not stripped</b>

This has not been stripped, so I can profile node and see more than just hex. If the result is stripped, configure your build system not to run strip(1) on the output binaries.

Kernel-level symbols are in the kernel debuginfo package, or when the kernel is compiled with CONFIG_KALLSYMS.

4.3. JIT Symbols (Java, Node.js)

Programs that have virtual machines (VMs), like Java’s JVM and node’s v8, execute their own virtual processor, which has its own way of executing functions and managing stacks. If you profile these using perf_events, you’ll see symbols for the VM engine, which have some use (eg, to identify if time is spent in GC), but you won’t see the language-level context you might be expecting. Eg, you won’t see Java classes and methods.

perf_events has JIT support to solve this, which requires the VM to maintain a /tmp/perf-PID.map file for symbol translation. Java can do this with perf-map-agent, and Node.js 0.11.13+ with –perf_basic_prof. See my blog post Node.js flame graphs on Linux for the steps.

Note that Java may not show full stacks to begin with, due to hotspot on x86 omitting the frame pointer (just like gcc). On newer versions (JDK 8u60+), you can use the -XX:+PreserveFramePointer option to fix this behavior, and profile fully using perf. See my Netflix Tech Blog post, Java in Flames, for a full writeup, and my Java flame graphs section, which links to an older patch and includes an example resulting flame graph. I also summarized the latest in my JavaOne 2016 talk Java Performance Analysis on Linux with Flame Graphs.

4.4 Stack Traces

Always compile with frame pointers. Omitting frame pointers is an evil compiler optimization that breaks debuggers, and sadly, is often the default. Without them, you may see incomplete stacks from perf_events, like seen in the earlier sshd symbols example. There are three ways to fix this: either using dwarf data to unwind the stack, using last branch record (LBR) if available (a processor feature), or returning the frame pointers.

Dwarf

Since about the 3.9 kernel, perf_events has supported a workaround for missing frame pointers in user-level stacks: libunwind, which uses dwarf. This can be enabled using “–call-graph dwarf” (or “-g dwarf”).

Frame Pointers

The earlier sshd example was a default build of OpenSSH, which uses compiler optimizations (-O2), which in this case has omitted the frame pointer. Here’s how it looks after recompiling OpenSSH with -fno-omit-frame-pointer:

100.00% sshd libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

|

--- __GI___connect_internal

|

|--30.00%-- add_one_listen_addr.isra.0

| add_listen_addr

| fill_default_server_options

| main

| __libc_start_main

|

|--20.00%-- __nscd_get_mapping

| __nscd_get_map_ref

|

|--20.00%-- __nscd_open_socket

--30.00%-- [...]

Now the ancestry from add_one_listen_addr() can be seen, down to main() and __libc_start_main().

The kernel can suffer the same problem. Here’s an example CPU profile collected on an idle server, with stack traces (-g):

99.97% swapper [kernel.kallsyms] [k] default_idle

|

--- default_idle

0.03% sshd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] iowrite16

|

--- iowrite16

__write_nocancel

(nil)

The kernel stack traces are incomplete. Now a similar profile with CONFIG_FRAME_POINTER=y:

99.97% swapper [kernel.kallsyms] [k] default_idle

|

--- default_idle

cpu_idle

|

|--87.50%-- start_secondary

|

--12.50%-- rest_init

start_kernel

x86_64_start_reservations

x86_64_start_kernel

0.03% sshd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] iowrite16

|

--- iowrite16

vp_notify

virtqueue_kick

start_xmit

dev_hard_start_xmit

sch_direct_xmit

dev_queue_xmit

ip_finish_output

ip_output

ip_local_out

ip_queue_xmit

tcp_transmit_skb

tcp_write_xmit

__tcp_push_pending_frames

tcp_sendmsg

inet_sendmsg

sock_aio_write

do_sync_write

vfs_write

sys_write

system_call_fastpath

__write_nocancel

Much better — the entire path from the write() syscall (__write_nocancel) to iowrite16() can be seen.

Also see the Building section for other notes about building perf_events.

4.5. Audience

To use perf_events, you’ll either:

- Develop your own commands

- Run example commands

Developing new invocations of perf_events requires the study of kernel and application code, which isn’t for everyone. Many more people will use perf_events by running commands developed by other people, like the examples on this page. This can work out fine: your organization may only need one or two people who can develop perf_events commands or source them, and then share them for use by the entire operation and support groups.

Either way, you need to know the capabilities of perf_events so you know when to reach for it, whether that means searching for an example command or writing your own. One goal of the examples that follow is just to show you what can be done, to help you learn these capabilities. You should also browse examples on other sites (Links).

If you’ve never used perf_events before, you may want to test before production use (it has had kernel panic bugs in the past). My experience has been a good one (no panics).

4.6. Usage

perf_events provides a command line tool, perf, and subcommands for various profiling activities. This is a single interface for the different instrumentation frameworks that provide the various events.

The perf command alone will list the subcommands; here is perf version 4.10 (for the Linux 4.10 kernel):

# <b>perf</b> usage: perf [--version] [--help] [OPTIONS] COMMAND [ARGS] The most commonly used perf commands are: annotate Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display annotated code archive Create archive with object files with build-ids found in perf.data file bench General framework for benchmark suites buildid-cache Manage build-id cache. buildid-list List the buildids in a perf.data file config Get and set variables in a configuration file. data Data file related processing diff Read perf.data files and display the differential profile evlist List the event names in a perf.data file inject Filter to augment the events stream with additional information kmem Tool to trace/measure kernel memory properties kvm Tool to trace/measure kvm guest os list List all symbolic event types lock Analyze lock events mem Profile memory accesses record Run a command and record its profile into perf.data report Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display the profile sched Tool to trace/measure scheduler properties (latencies) script Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display trace output stat Run a command and gather performance counter statistics test Runs sanity tests. timechart Tool to visualize total system behavior during a workload top System profiling tool. probe Define new dynamic tracepoints trace strace inspired tool See 'perf help COMMAND' for more information on a specific command.

Apart from separate help for each subcommand, there is also documentation in the kernel source under tools/perf/Documentation. perf has evolved, with different functionality added over time, so on an older kernel you may be missing some subcommands or functionality. Also, its usage may not feel consistent as you switch between activities. It’s best to think of it as a multi-tool.

perf_events can instrument in three ways (using the perf_events terminology):

- counting events in-kernel context, where a summary of counts is printed by perf. This mode does not generate a perf.data file.

- sampling events, which writes event data to a kernel buffer, which is read at a gentle asynchronous rate by the perf command to write to the perf.data file. This file is then read by the perf report or perf script commands.

- bpf programs on events, a new feature in Linux 4.4+ kernels that can execute custom user-defined programs in kernel space, which can perform efficient filters and summaries of the data. Eg, efficiently-measured latency histograms.

Try starting by counting events using the perf stat command, to see if this is sufficient. This subcommand costs the least overhead.

When using the sampling mode with perf record, you’ll need to be a little careful about the overheads, as the capture files can quickly become hundreds of Mbytes. It depends on the rate of the event you are tracing: the more frequent, the higher the overhead and larger the perf.data size.

To really cut down overhead and generate more advanced summaries, write BPF programs executed by perf. See the eBPF section.

4.7. Usage Examples

These example sequences have been chosen to illustrate some different ways that perf is used, from gathering to reporting.

Performance counter summaries, including IPC, for the gzip command:

# <b>perf stat gzip largefile</b>

Count all scheduler process events for 5 seconds, and count by tracepoint:

# <b>perf stat -e 'sched:sched_process_*' -a sleep 5</b>

Trace all scheduler process events for 5 seconds, and count by both tracepoint and process name:

# <b>perf record -e 'sched:sched_process_*' -a sleep 5</b> # <b>perf report</b>

Trace all scheduler process events for 5 seconds, and dump per-event details:

# <b>perf record -e 'sched:sched_process_*' -a sleep 5</b> # <b>perf script</b>

Trace read() syscalls, when requested bytes is less than 10:

# <b>perf record -e 'syscalls:sys_enter_read' --filter 'count < 10' -a</b>

Sample CPU stacks at 99 Hertz, for 5 seconds:

# <b>perf record -F 99 -ag -- sleep 5</b> # <b>perf report</b>

Dynamically instrument the kernel tcp_sendmsg() function, and trace it for 5 seconds, with stack traces:

# <b>perf probe --add tcp_sendmsg</b> # <b>perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -ag -- sleep 5</b> # <b>perf probe --del tcp_sendmsg</b> # <b>perf report</b>

Deleting the tracepoint (–del) wasn’t necessary; I included it to show how to return the system to its original state.

Caveats

The use of -p PID as a filter doesn’t work properly on some older kernel versions (Linux 3.x): perf hits 100% CPU and needs to be killed. It’s annoying. The workaround is to profile all CPUs (-a), and filter PIDs later.

4.8. Special Usage

There’s a number of subcommands that provide special purpose functionality. These include:

- perf c2c (Linux 4.10+): cache-2-cache and cacheline false sharing analysis.

- perf kmem: kernel memory allocation analysis.

- perf kvm: KVM virtual guest analysis.

- perf lock: lock analysis.

- perf mem: memory access analysis.

- perf sched: kernel scheduler statistics. Examples.

These make use of perf’s existing instrumentation capabilities, recording selected events and reporting them in custom ways.

5. Events

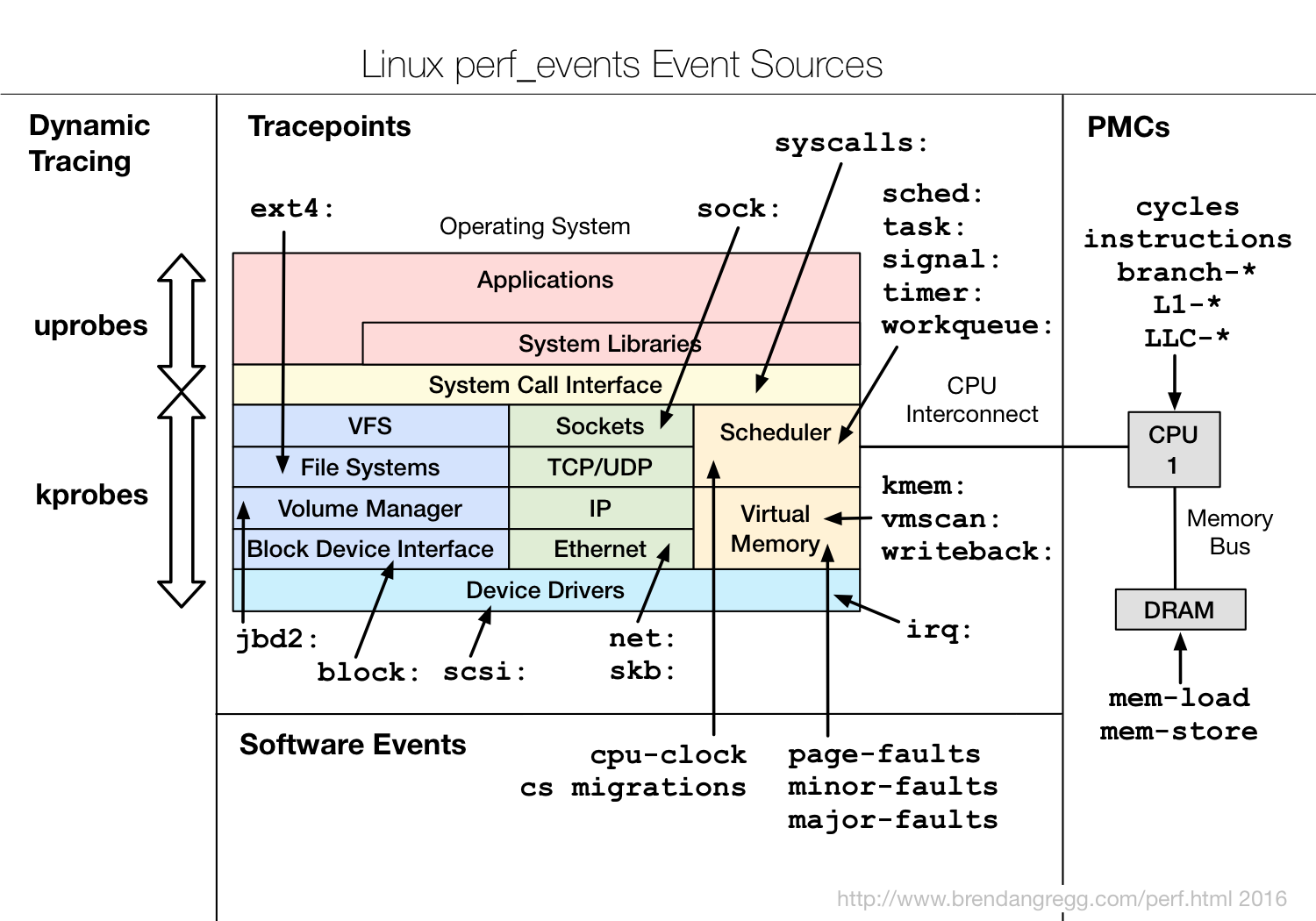

perf_events instruments “events”, which are a unified interface for different kernel instrumentation frameworks. The following map (from my SCaLE13x talk) illustrates the event sources:

- Hardware Events: CPU performance monitoring counters.

- Software Events: These are low level events based on kernel counters. For example, CPU migrations, minor faults, major faults, etc.

- Kernel Tracepoint Events: This are static kernel-level instrumentation points that are hardcoded in interesting and logical places in the kernel.

- User Statically-Defined Tracing (USDT): These are static tracepoints for user-level programs and applications.

- Dynamic Tracing: Software can be dynamically instrumented, creating events in any location. For kernel software, this uses the kprobes framework. For user-level software, uprobes.

- Timed Profiling: Snapshots can be collected at an arbitrary frequency, using perf record -FHz. This is commonly used for CPU usage profiling, and works by creating custom timed interrupt events.

Details about the events can be collected, including timestamps, the code path that led to it, and other specific details. The capabilities of perf_events are enormous, and you’re likely to only ever use a fraction.

Currently available events can be listed using the list subcommand:

# <b>perf list</b>

List of pre-defined events (to be used in -e):

cpu-cycles OR cycles [Hardware event]

instructions [Hardware event]

cache-references [Hardware event]

cache-misses [Hardware event]

branch-instructions OR branches [Hardware event]

branch-misses [Hardware event]

bus-cycles [Hardware event]

stalled-cycles-frontend OR idle-cycles-frontend [Hardware event]

stalled-cycles-backend OR idle-cycles-backend [Hardware event]

ref-cycles [Hardware event]

cpu-clock [Software event]

task-clock [Software event]

page-faults OR faults [Software event]

context-switches OR cs [Software event]

cpu-migrations OR migrations [Software event]

minor-faults [Software event]

major-faults [Software event]

alignment-faults [Software event]

emulation-faults [Software event]

L1-dcache-loads [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-load-misses [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-stores [Hardware cache event]

[...]

rNNN [Raw hardware event descriptor]

cpu/t1=v1[,t2=v2,t3 ...]/modifier [Raw hardware event descriptor]

(see 'man perf-list' on how to encode it)

mem:<addr>[:access] [Hardware breakpoint]

probe:tcp_sendmsg [Tracepoint event]

[...]

sched:sched_process_exec [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_process_fork [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_process_wait [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_wait_task [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_process_exit [Tracepoint event]

[...]

# <b>perf list | wc -l</b>

657

When you use dynamic tracing, you are extending this list. The probe:tcp_sendmsg tracepoint in this list is an example, which I added by instrumenting tcp_sendmsg(). Profiling (sampling) events are not listed.

5.1. Hardware Events (PMCs)

perf_events began life as a tool for instrumenting the processor’s performance monitoring unit (PMU) hardware counters, also called performance monitoring counters (PMCs), or performance instrumentation counters (PICs). These instrument low-level processor activity, for example, CPU cycles, instructions retired, memory stall cycles, level 2 cache misses, etc. Some will be listed as Hardware Cache Events.

PMCs are documented in the Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 3B: System Programming Guide, Part 2 and the BIOS and Kernel Developer’s Guide (BKDG) For AMD Family 10h Processors. There are thousands of different PMCs available.

A typical processor will implement PMCs in the following way: only a few or several can be recorded at the same time, from the many thousands that are available. This is because they are a fixed hardware resource on the processor (a limited number of registers), and are programmed to begin counting the selected events.

For examples of using PMCs, see 6.1. CPU Statistics.

5.2. Kernel Tracepoints

These tracepoints are hard coded in interesting and logical locations of the kernel, so that higher-level behavior can be easily traced. For example, system calls, TCP events, file system I/O, disk I/O, etc. These are grouped into libraries of tracepoints; eg, “sock:” for socket events, “sched:” for CPU scheduler events. A key value of tracepoints is that they should have a stable API, so if you write tools that use them on one kernel version, they should work on later versions as well.

Tracepoints are usually added to kernel code by placing a macro from include/trace/events/*. XXX cover implementation.

Summarizing the tracepoint library names and numbers of tracepoints, on my Linux 4.10 system:

# <b>perf list | awk -F: '/Tracepoint event/ { lib[$1]++ } END {

for (l in lib) { printf " %-16.16s %d\n", l, lib[l] } }' | sort | column</b>

alarmtimer 4 i2c 8 page_isolation 1 swiotlb 1

block 19 iommu 7 pagemap 2 syscalls 614

btrfs 51 irq 5 power 22 task 2

cgroup 9 irq_vectors 22 printk 1 thermal 7

clk 14 jbd2 16 random 15 thermal_power_ 2

cma 2 kmem 12 ras 4 timer 13

compaction 14 libata 6 raw_syscalls 2 tlb 1

cpuhp 3 mce 1 rcu 1 udp 1

dma_fence 8 mdio 1 regmap 15 vmscan 15

exceptions 2 migrate 2 regulator 7 vsyscall 1

ext4 95 mmc 2 rpm 4 workqueue 4

fib 3 module 5 sched 24 writeback 30

fib6 1 mpx 5 scsi 5 x86_fpu 14

filelock 10 msr 3 sdt_node 1 xen 35

filemap 2 napi 1 signal 2 xfs 495

ftrace 1 net 10 skb 3 xhci-hcd 9

gpio 2 nmi 1 sock 2

huge_memory 4 oom 1 spi 7

These include:

- block: block device I/O

- ext4: file system operations

- kmem: kernel memory allocation events

- random: kernel random number generator events

- sched: CPU scheduler events

- syscalls: system call enter and exits

- task: task events

It’s worth checking the list of tracepoints after every kernel upgrade, to see if any are new. The value of adding them has been debated from time to time, with it wondered how many people will use them (I do). There is a balance to aim for: I’d include the smallest number of probes that sufficiently covers common needs, and anything unusual or uncommon can be left to dynamic tracing.

For examples of using tracepoints, see Static Kernel Tracing.

5.3. User-Level Statically Defined Tracing (USDT)

Similar to kernel tracepoints, these are hardcoded (usually by placing macros) in the application source at logical and interesting locations, and presented (event name and arguments) as a stable API. Many applications already include tracepoints, added to support DTrace. However, many of these applications do not compile them in by default on Linux. Often you need to compile the application yourself using a –with-dtrace flag.

For example, compiling USDT events with this version of Node.js:

$ <b>sudo apt-get install systemtap-sdt-dev</b> # adds "dtrace", used by node build $ <b>wget https://nodejs.org/dist/v4.4.1/node-v4.4.1.tar.gz</b> $ <b>tar xvf node-v4.4.1.tar.gz </b> $ <b>cd node-v4.4.1</b> $ <b>./configure --with-dtrace</b> $ <b>make -j 8</b>

To check that the resulting node binary has probes included:

$ <b>readelf -n node</b>

Displaying notes found at file offset 0x00000254 with length 0x00000020:

Owner Data size Description

GNU 0x00000010 NT_GNU_ABI_TAG (ABI version tag)

OS: Linux, ABI: 2.6.32

Displaying notes found at file offset 0x00000274 with length 0x00000024:

Owner Data size Description

GNU 0x00000014 NT_GNU_BUILD_ID (unique build ID bitstring)

Build ID: 1e01659b0aecedadf297b2c56c4a2b536ae2308a

Displaying notes found at file offset 0x00e70994 with length 0x000003c4:

Owner Data size Description

stapsdt 0x0000003c NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>gc__start</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc14e4, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x000000000147095c

Arguments: 4@%esi 4@%edx 8@%rdi

stapsdt 0x0000003b NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>gc__done</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc14f4, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x000000000147095e

Arguments: 4@%esi 4@%edx 8@%rdi

stapsdt 0x00000067 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>http__server__response</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc1894, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x0000000001470956

Arguments: 8@%rax 8@-1144(%rbp) -4@-1148(%rbp) -4@-1152(%rbp)

stapsdt 0x00000061 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>net__stream__end</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc1c44, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x0000000001470952

Arguments: 8@%rax 8@-1144(%rbp) -4@-1148(%rbp) -4@-1152(%rbp)

stapsdt 0x00000068 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>net__server__connection</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc1ff4, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x0000000001470950

Arguments: 8@%rax 8@-1144(%rbp) -4@-1148(%rbp) -4@-1152(%rbp)

stapsdt 0x00000060 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>http__client__response</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc23c5, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x000000000147095a

Arguments: 8@%rdx 8@-1144(%rbp) -4@%eax -4@-1152(%rbp)

stapsdt 0x00000089 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>http__client__request</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc285e, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x0000000001470958

Arguments: 8@%rax 8@%rdx 8@-2184(%rbp) -4@-2188(%rbp) 8@-2232(%rbp) 8@-2240(%rbp) -4@-2192(%rbp)

stapsdt 0x00000089 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: node

Name: <b>http__server__request</b>

Location: 0x0000000000dc2e69, Base: 0x000000000112e064, Semaphore: 0x0000000001470954

Arguments: 8@%r14 8@%rax 8@-4344(%rbp) -4@-4348(%rbp) 8@-4304(%rbp) 8@-4312(%rbp) -4@-4352(%rbp)

For examples of using USDT events, see Static User Tracing.

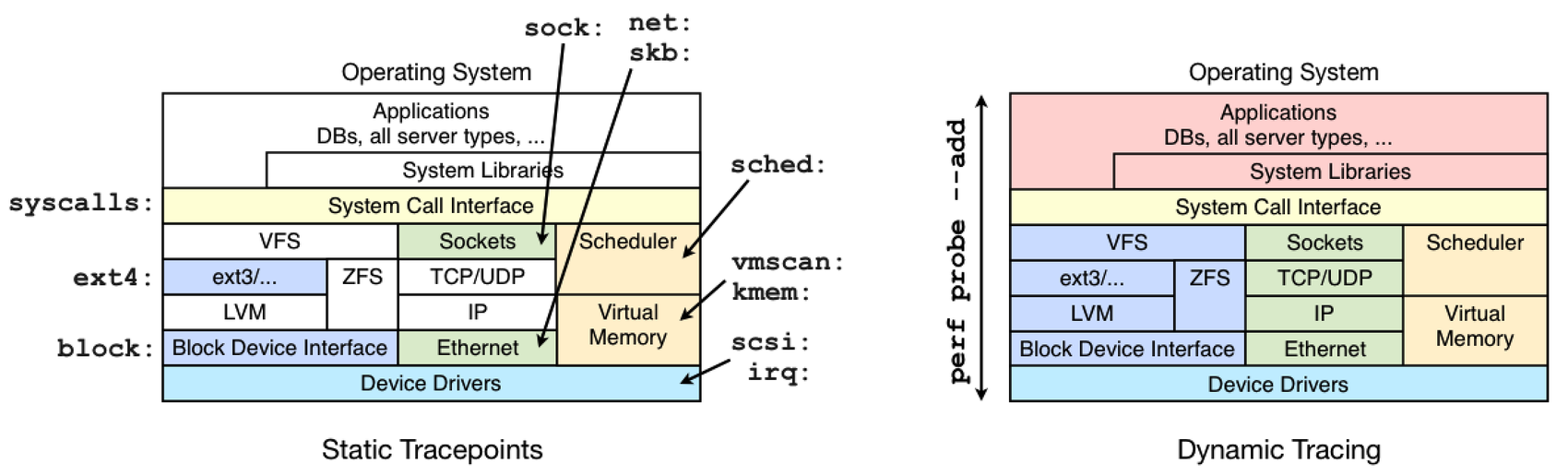

5.4. Dynamic Tracing

The difference between tracepoints and dynamic tracing is shown in the following figure, which illustrates the coverage of common tracepoint libraries:

While dynamic tracing can see everything, it’s also an unstable interface since it is instrumenting raw code. That means that any dynamic tracing tools you develop may break after a kernel patch or update. Try to use the static tracepoints first, since their interface should be much more stable. They can also be easier to use and understand, since they have been designed with a tracing end-user in mind.

One benefit of dynamic tracing is that it can be enabled on a live system without restarting anything. You can take an already-running kernel or application and then begin dynamic instrumentation, which (safely) patches instructions in memory to add instrumentation. That means there is zero overhead or tax for this feature until you begin using it. One moment your binary is running unmodified and at full speed, and the next, it’s running some extra instrumentation instructions that you dynamically added. Those instructions should eventually be removed once you’ve finished using your session of dynamic tracing.

The overhead while dynamic tracing is in use, and extra instructions are being executed, is relative to the frequency of instrumented events multiplied by the work done on each instrumentation.

For examples of using dynamic tracing, see 6.5. Dynamic Tracing.

6. Examples

These are some examples of perf_events, collected from a variety of 3.x Linux systems.

6.1. CPU Statistics

The perf stat command instruments and summarizes key CPU counters (PMCs). This is from perf version 3.5.7.2:

# <b>perf stat gzip file1</b>

Performance counter stats for 'gzip file1':

1920.159821 task-clock # 0.991 CPUs utilized

13 context-switches # 0.007 K/sec

0 CPU-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

258 page-faults # 0.134 K/sec

5,649,595,479 cycles # 2.942 GHz [83.43%]

1,808,339,931 stalled-cycles-frontend # 32.01% frontend cycles idle [83.54%]

1,171,884,577 stalled-cycles-backend # 20.74% backend cycles idle [66.77%]

8,625,207,199 instructions # 1.53 insns per cycle

# 0.21 stalled cycles per insn [83.51%]

1,488,797,176 branches # 775.351 M/sec [82.58%]

53,395,139 branch-misses # 3.59% of all branches [83.78%]

1.936842598 seconds time elapsed

This includes instructions per cycle (IPC), labled “insns per cycle”, or in earlier versions, “IPC”. This is a commonly examined metric, either IPC or its invert, CPI. Higher IPC values mean higher instruction throughput, and lower values indicate more stall cycles. I’d generally interpret high IPC values (eg, over 1.0) as good, indicating optimal processing of work. However, I’d want to double check what the instructions are, in case this is due to a spin loop: a high rate of instructions, but a low rate of actual work completed.

There are some advanced metrics now included in perf stat: frontend cycles idle, backend cycles idle, and stalled cycles per insn. To really understand these, you’ll need some knowledge of CPU microarchitecture.

CPU Microarchitecture

The frontend and backend metrics refer to the CPU pipeline, and are also based on stall counts. The frontend processes CPU instructions, in order. It involves instruction fetch, along with branch prediction, and decode. The decoded instructions become micro-operations (uops) which the backend processes, and it may do so out of order. For a longer summary of these components, see Shannon Cepeda’s great posts on frontend and backend.

The backend can also process multiple uops in parallel; for modern processors, three or four. Along with pipelining, this is how IPC can become greater than one, as more than one instruction can be completed (“retired”) per CPU cycle.

Stalled cycles per instruction is similar to IPC (inverted), however, only counting stalled cycles, which will be for memory or resource bus access. This makes it easy to interpret: stalls are latency, reduce stalls. I really like it as a metric, and hope it becomes as commonplace as IPC/CPI. Lets call it SCPI.

Detailed Mode

There is a “detailed” mode for perf stat:

# <b>perf stat -d gzip file1</b>

Performance counter stats for 'gzip file1':

1610.719530 task-clock # 0.998 CPUs utilized

20 context-switches # 0.012 K/sec

0 CPU-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

258 page-faults # 0.160 K/sec

5,491,605,997 cycles # 3.409 GHz [40.18%]

1,654,551,151 stalled-cycles-frontend # 30.13% frontend cycles idle [40.80%]

1,025,280,350 stalled-cycles-backend # 18.67% backend cycles idle [40.34%]

8,644,643,951 instructions # 1.57 insns per cycle

# 0.19 stalled cycles per insn [50.89%]

1,492,911,665 branches # 926.860 M/sec [50.69%]

53,471,580 branch-misses # 3.58% of all branches [51.21%]

1,938,889,736 L1-dcache-loads # 1203.741 M/sec [49.68%]

154,380,395 L1-dcache-load-misses # 7.96% of all L1-dcache hits [49.66%]

0 LLC-loads # 0.000 K/sec [39.27%]

0 LLC-load-misses # 0.00% of all LL-cache hits [39.61%]

1.614165346 seconds time elapsed

This includes additional counters for Level 1 data cache events, and last level cache (LLC) events.

Specific Counters

Hardware cache event counters, seen in perf list, can be instrumented. Eg:

# <b>perf list | grep L1-dcache</b>

L1-dcache-loads [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-load-misses [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-stores [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-store-misses [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-prefetches [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-prefetch-misses [Hardware cache event]

# <b>perf stat -e L1-dcache-loads,L1-dcache-load-misses,L1-dcache-stores gzip file1</b>

Performance counter stats for 'gzip file1':

1,947,551,657 L1-dcache-loads

153,829,652 L1-dcache-misses

# 7.90% of all L1-dcache hits

1,171,475,286 L1-dcache-stores

1.538038091 seconds time elapsed

The percentage printed is a convenient calculation that perf_events has included, based on the counters I specified. If you include the “cycles” and “instructions” counters, it will include an IPC calculation in the output.

These hardware events that can be measured are often specific to the processor model. Many may not be available from within a virtualized environment.

Raw Counters

The Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 3B: System Programming Guide, Part 2 and the BIOS and Kernel Developer’s Guide (BKDG) For AMD Family 10h Processors are full of interesting counters, but most cannot be found in perf list. If you find one you want to instrument, you can specify it as a raw event with the format: rUUEE, where UU == umask, and EE == event number. Here’s an example where I’ve added a couple of raw counters:

# <b>perf stat -e cycles,instructions,r80a2,r2b1 gzip file1</b>

Performance counter stats for 'gzip file1':

5,586,963,328 cycles # 0.000 GHz

8,608,237,932 instructions # 1.54 insns per cycle

9,448,159 raw 0x80a2

11,855,777,803 raw 0x2b1

1.588618969 seconds time elapsed

If I did this right, then r80a2 has instrumented RESOURCE_STALLS.OTHER, and r2b1 has instrumented UOPS_DISPATCHED.CORE: the number of uops dispatched each cycle. It’s easy to mess this up, and you’ll want to double check that you are on the right page of the manual for your processor.

If you do find an awesome raw counter, please suggest it be added as an alias in perf_events, so we all can find it in perf list.

Other Options

The perf subcommands, especially perf stat, have an extensive option set which can be listed using “-h”. I’ve included the full output for perf stat here from version 3.9.3, not as a reference, but as an illustration of the interface:

# <b>perf stat -h</b>

usage: perf stat [<options>] [<command>]

-e, --event <event> event selector. use 'perf list' to list available events

--filter <filter>

event filter

-i, --no-inherit child tasks do not inherit counters

-p, --pid <pid> stat events on existing process id

-t, --tid <tid> stat events on existing thread id

-a, --all-cpus system-wide collection from all CPUs

-g, --group put the counters into a counter group

-c, --scale scale/normalize counters

-v, --verbose be more verbose (show counter open errors, etc)

-r, --repeat <n> repeat command and print average + stddev (max: 100)

-n, --null null run - dont start any counters

-d, --detailed detailed run - start a lot of events

-S, --sync call sync() before starting a run

-B, --big-num print large numbers with thousands' separators

-C, --cpu <cpu> list of cpus to monitor in system-wide

-A, --no-aggr disable CPU count aggregation

-x, --field-separator <separator>

print counts with custom separator

-G, --cgroup <name> monitor event in cgroup name only

-o, --output <file> output file name

--append append to the output file

--log-fd <n> log output to fd, instead of stderr

--pre <command> command to run prior to the measured command

--post <command> command to run after to the measured command

-I, --interval-print <n>

print counts at regular interval in ms (>= 100)

--aggr-socket aggregate counts per processor socket

Options such as –repeat, –sync, –pre, and –post can be quite useful when doing automated testing or micro-benchmarking.

6.2. Timed Profiling

perf_events can profile CPU usage based on sampling the instruction pointer or stack trace at a fixed interval (timed profiling).

Sampling CPU stacks at 99 Hertz (-F 99), for the entire system (-a, for all CPUs), with stack traces (-g, for call graphs), for 10 seconds:

# <b>perf record -F 99 -a -g -- sleep 30</b> [ perf record: Woken up 9 times to write data ] [ perf record: Captured and wrote 3.135 MB perf.data (~136971 samples) ] # ls -lh perf.data -rw------- 1 root root 3.2M Jan 26 07:26 perf.data

The choice of 99 Hertz, instead of 100 Hertz, is to avoid accidentally sampling in lockstep with some periodic activity, which would produce skewed results. This is also coarse: you may want to increase that to higher rates (eg, up to 997 Hertz) for finer resolution, especially if you are sampling short bursts of activity and you’d still like enough resolution to be useful. Bear in mind that higher frequencies means higher overhead.

The perf.data file can be processed in a variety of ways. On recent versions, the perf report command launches an ncurses navigator for call graph inspection. Older versions of perf (or if use –stdio in the new version) print the call graph as a tree, annotated with percentages:

# <b>perf report --stdio</b>

# ========

# captured on: Mon Jan 26 07:26:40 2014

# hostname : dev2

# os release : 3.8.6-ubuntu-12-opt

# perf version : 3.8.6

# arch : x86_64

# nrcpus online : 8

# nrcpus avail : 8

# cpudesc : Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU X5675 @ 3.07GHz

# cpuid : GenuineIntel,6,44,2

# total memory : 8182008 kB

# cmdline : /usr/bin/perf record -F 99 -a -g -- sleep 30

# event : name = cpu-clock, type = 1, config = 0x0, config1 = 0x0, config2 = ...

# HEADER_CPU_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# HEADER_NUMA_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# pmu mappings: software = 1, breakpoint = 5

# ========

#

# Samples: 22K of event 'cpu-clock'

# Event count (approx.): 22751

#

# Overhead Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ....... ................. ...............................

#

94.12% dd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore

|

--- _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore

|

|--96.67%-- extract_buf

| extract_entropy_user

| urandom_read

| vfs_read

| sys_read

| system_call_fastpath

| read

|

|--1.69%-- account

| |

| |--99.72%-- extract_entropy_user

| | urandom_read

| | vfs_read

| | sys_read

| | system_call_fastpath

| | read

| --0.28%-- [...]

|

|--1.60%-- mix_pool_bytes.constprop.17

[...]

This tree starts with the on-CPU functions and works back through the ancestry. This approach is called a “callee based call graph”. This can be flipped by using -G for an “inverted call graph”, or by using the “caller” option to -g/–call-graph, instead of the “callee” default.

The hottest (most frequent) stack trace in this perf call graph occurred in 90.99% of samples, which is the product of the overhead percentage and top stack leaf (94.12% x 96.67%, which are relative rates). perf report can also be run with “-g graph” to show absolute overhead rates, in which case “90.99%” is directly displayed on the stack leaf:

94.12% dd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore

|

--- _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore

|

|--90.99%-- extract_buf

[...]

If user-level stacks look incomplete, you can try perf record with “–call-graph dwarf” as a different technique to unwind them. See the Stacks section.

The output from perf report can be many pages long, which can become cumbersome to read. Try generating Flame Graphs from the same data.

6.3. Event Profiling

Apart from sampling at a timed interval, taking samples triggered by CPU hardware counters is another form of CPU profiling, which can be used to shed more light on cache misses, memory stall cycles, and other low-level processor events. The available events can be found using perf list:

# <b>perf list | grep Hardware</b> cpu-cycles OR cycles [Hardware event] instructions [Hardware event] cache-references [Hardware event] cache-misses [Hardware event] branch-instructions OR branches [Hardware event] branch-misses [Hardware event] bus-cycles [Hardware event] stalled-cycles-frontend OR idle-cycles-frontend [Hardware event] stalled-cycles-backend OR idle-cycles-backend [Hardware event] ref-cycles [Hardware event] L1-dcache-loads [Hardware cache event] L1-dcache-load-misses [Hardware cache event] L1-dcache-stores [Hardware cache event] L1-dcache-store-misses [Hardware cache event] [...]

For many of these, gathering a stack on every occurrence would induce far too much overhead, and would slow down the system and change the performance characteristics of the target. It’s usually sufficient to only instrument a small fraction of their occurrences, rather than all of them. This can be done by specifying a threshold for triggering event collection, using “-c” and a count.

For example, the following one-liner instruments Level 1 data cache load misses, collecting a stack trace for one in every 10,000 occurrences:

# <b>perf record -e L1-dcache-load-misses -c 10000 -ag -- sleep 5</b>

The mechanics of “-c count” are implemented by the processor, which only interrupts the kernel when the threshold has been reached.

See the earlier Raw Counters section for an example of specifying a custom counter.

PEBS

XXX: fill me in. Need to cover problems and PEBS support and other caveats.

If PEBS isn’t working for you, check dmesg:

# dmesg | grep -i pebs [ 0.387014] Performance Events: PEBS fmt1+, SandyBridge events, 16-deep LBR, full-width counters, Intel PMU driver. [ 0.387034] core: PEBS disabled due to CPU errata, please upgrade microcode

The fix (on Intel):

# apt-get install -y intel-microcode [...] intel-microcode: microcode will be updated at next boot Processing triggers for initramfs-tools (0.125ubuntu5) ... update-initramfs: Generating /boot/initrd.img-4.8.0-41-generic # reboot (system reboots) # dmesg | grep -i pebs [ 0.386596] Performance Events: PEBS fmt1+, SandyBridge events, 16-deep LBR, full-width counters, Intel PMU driver. #

6.4. Static Kernel Tracing

The following examples demonstrate static tracing: the instrumentation of tracepoints and other static events.

Counting Syscalls

The following simple one-liner counts system calls for the executed command, and prints a summary (of non-zero counts):

# <b>perf stat -e 'syscalls:sys_enter_*' gzip file1 2>&1 | awk '$1 != 0'</b>

Performance counter stats for 'gzip file1':

1 syscalls:sys_enter_utimensat

1 syscalls:sys_enter_unlink

5 syscalls:sys_enter_newfstat

1,603 syscalls:sys_enter_read

3,201 syscalls:sys_enter_write

5 syscalls:sys_enter_access

1 syscalls:sys_enter_fchmod

1 syscalls:sys_enter_fchown

6 syscalls:sys_enter_open

9 syscalls:sys_enter_close

8 syscalls:sys_enter_mprotect

1 syscalls:sys_enter_brk

1 syscalls:sys_enter_munmap

1 syscalls:sys_enter_set_robust_list

1 syscalls:sys_enter_futex

1 syscalls:sys_enter_getrlimit

5 syscalls:sys_enter_rt_sigprocmask

14 syscalls:sys_enter_rt_sigaction

1 syscalls:sys_enter_exit_group

1 syscalls:sys_enter_set_tid_address

14 syscalls:sys_enter_mmap

1.543990940 seconds time elapsed

In this case, a gzip command was analyzed. The report shows that there were 3,201 write() syscalls, and half that number of read() syscalls. Many of the other syscalls will be due to process and library initialization.

A similar report can be seen using strace -c, the system call tracer, however it may induce much higher overhead than perf, as perf buffers data in-kernel.

perf vs strace

To explain the difference a little further: the current implementation of strace uses ptrace(2) to attach to the target process and stop it during system calls, like a debugger. This is violent, and can cause serious overhead. To demonstrate this, the following syscall-heavy program was run by itself, with perf, and with strace. I’ve only included the line of output that shows its performance:

# <b>dd if=/dev/zero of=/dev/null bs=512 count=10000k</b> 5242880000 bytes (5.2 GB) copied, 3.53031 s, 1.5 GB/s # <b>perf stat -e 'syscalls:sys_enter_*' dd if=/dev/zero of=/dev/null bs=512 count=10000k</b> 5242880000 bytes (5.2 GB) copied, 9.14225 s, 573 MB/s # <b>strace -c dd if=/dev/zero of=/dev/null bs=512 count=10000k</b> 5242880000 bytes (5.2 GB) copied, 218.915 s, 23.9 MB/s

With perf, the program ran 2.5x slower. But with strace, it ran 62x slower. That’s likely to be a worst-case result: if syscalls are not so frequent, the difference between the tools will not be as great.

Recent version of perf have included a trace subcommand, to provide some similar functionality to strace, but with much lower overhead.

New Processes

Tracing new processes triggered by a “man ls”:

# <b>perf record -e sched:sched_process_exec -a</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.064 MB perf.data (~2788 samples) ]

# <b>perf report -n --sort comm --stdio</b>

[...]

# Overhead Samples Command

# ........ ............ .......

#

11.11% 1 troff

11.11% 1 tbl

11.11% 1 preconv

11.11% 1 pager

11.11% 1 nroff

11.11% 1 man

11.11% 1 locale

11.11% 1 grotty

11.11% 1 groff

Nine different commands were executed, each once. I used -n to print the “Samples” column, and “–sort comm” to customize the remaining columns.

This works by tracing sched:sched_process_exec, when a process runs exec() to execute a different binary. This is often how new processes are created, but not always. An application may fork() to create a pool of worker processes, but not exec() a different binary. An application may also reexec: call exec() again, on itself, usually to clean up its address space. In that case, it’s will be seen by this exec tracepoint, but it’s not a new process.

The sched:sched_process_fork tracepoint can be traced to only catch new processes, created via fork(). The downside is that the process identified is the parent, not the new target, as the new process has yet to exec() it’s final program.

Outbound Connections

There can be times when it’s useful to double check what network connections are initiated by a server, from which processes, and why. You might be surprised. These connections can be important to understand, as they can be a source of latency.

For this example, I have a completely idle ubuntu server, and while tracing I’ll login to it using ssh. I’m going to trace outbound connections via the connect() syscall. Given that I’m performing an inbound connection over SSH, will there be any outbound connections at all?

# <b>perf record -e syscalls:sys_enter_connect -a</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.057 MB perf.data (~2489 samples) ]

# <b>perf report --stdio</b>

# ========

# captured on: Tue Jan 28 10:53:38 2014

# hostname : ubuntu

# os release : 3.5.0-23-generic

# perf version : 3.5.7.2

# arch : x86_64

# nrcpus online : 2

# nrcpus avail : 2

# cpudesc : Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-3820QM CPU @ 2.70GHz

# cpuid : GenuineIntel,6,58,9

# total memory : 1011932 kB

# cmdline : /usr/bin/perf_3.5.0-23 record -e syscalls:sys_enter_connect -a

# event : name = syscalls:sys_enter_connect, type = 2, config = 0x38b, ...

# HEADER_CPU_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# HEADER_NUMA_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# ========

#

# Samples: 21 of event 'syscalls:sys_enter_connect'

# Event count (approx.): 21

#

# Overhead Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ....... .................. ...........................

#

52.38% sshd libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

19.05% groups libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

9.52% sshd libpthread-2.15.so [.] __connect_internal

9.52% mesg libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

9.52% bash libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

The report shows that sshd, groups, mesg, and bash are all performing connect() syscalls. Ring a bell?

The stack traces that led to the connect() can explain why:

# <b>perf record -e syscalls:sys_enter_connect -ag</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.057 MB perf.data (~2499 samples) ]

# <b>perf report --stdio</b>

[...]

55.00% sshd libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

|

--- __GI___connect_internal

|

|--27.27%-- add_one_listen_addr.isra.0

|

|--27.27%-- __nscd_get_mapping

| __nscd_get_map_ref

|

|--27.27%-- __nscd_open_socket

--18.18%-- [...]

20.00% groups libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

|

--- __GI___connect_internal

|

|--50.00%-- __nscd_get_mapping

| __nscd_get_map_ref

|

--50.00%-- __nscd_open_socket

10.00% mesg libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

|

--- __GI___connect_internal

|

|--50.00%-- __nscd_get_mapping

| __nscd_get_map_ref

|

--50.00%-- __nscd_open_socket

10.00% bash libc-2.15.so [.] __GI___connect_internal

|

--- __GI___connect_internal

|

|--50.00%-- __nscd_get_mapping

| __nscd_get_map_ref

|

--50.00%-- __nscd_open_socket

5.00% sshd libpthread-2.15.so [.] __connect_internal

|

--- __connect_internal

Ah, these are nscd calls: the name service cache daemon. If you see hexadecimal numbers and not function names, you will need to install debug info: see the earlier section on Symbols. These nscd calls are likely triggered by calling getaddrinfo(), which server software may be using to resolve IP addresses for logging, or for matching hostnames in config files. Browsing the stack traces should identify why.

For sshd, this was called via add_one_listen_addr(): a name that was only visible after adding the openssh-server-dbgsym package. Unfortunately, the stack trace doesn’t continue after add_one_listen_add(). I can browse the OpenSSH code to figure out the reasons we’re calling into add_one_listen_add(), or, I can get the stack traces to work. See the earlier section on Stack Traces.

I took a quick look at the OpenSSH code, and it looks like this code-path is due to parsing ListenAddress from the sshd_config file, which can contain either an IP address or a hostname.

Socket Buffers

Tracing the consumption of socket buffers, and the stack traces, is one way to identify what is leading to socket or network I/O.

# <b>perf record -e 'skb:consume_skb' -ag</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.065 MB perf.data (~2851 samples) ]

# <b>perf report</b>

[...]

74.42% swapper [kernel.kallsyms] [k] consume_skb

|

--- consume_skb

arp_process

arp_rcv

__netif_receive_skb_core

__netif_receive_skb

netif_receive_skb

virtnet_poll

net_rx_action

__do_softirq

irq_exit

do_IRQ

ret_from_intr

default_idle

cpu_idle

start_secondary

25.58% sshd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] consume_skb

|

--- consume_skb

dev_kfree_skb_any

free_old_xmit_skbs.isra.24

start_xmit

dev_hard_start_xmit

sch_direct_xmit

dev_queue_xmit

ip_finish_output

ip_output

ip_local_out

ip_queue_xmit

tcp_transmit_skb

tcp_write_xmit

__tcp_push_pending_frames

tcp_sendmsg

inet_sendmsg

sock_aio_write

do_sync_write

vfs_write

sys_write

system_call_fastpath

__write_nocancel

The swapper stack shows the network receive path, triggered by an interrupt. The sshd path shows writes.

6.5. Static User Tracing

Support was added in later 4.x series kernels. The following demonstrates Linux 4.10 (with an additional patchset), and tracing the Node.js USDT probes:

# <b>perf buildid-cache --add `which node`</b>

# <b>perf list | grep sdt_node</b>

sdt_node:gc__done [SDT event]

sdt_node:gc__start [SDT event]

sdt_node:http__client__request [SDT event]

sdt_node:http__client__response [SDT event]

sdt_node:http__server__request [SDT event]

sdt_node:http__server__response [SDT event]

sdt_node:net__server__connection [SDT event]

sdt_node:net__stream__end [SDT event]

# <b>perf record -e sdt_node:http__server__request -a</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.446 MB perf.data (3 samples) ]

# <b>perf script</b>

node 7646 [002] 361.012364: sdt_node:http__server__request: (dc2e69)

node 7646 [002] 361.204718: sdt_node:http__server__request: (dc2e69)

node 7646 [002] 361.363043: sdt_node:http__server__request: (dc2e69)

XXX fill me in, including how to use arguments.

If you are on an older kernel, say, Linux 4.4-4.9, you can probably get these to work with adjustments (I’ve even hacked them up with ftrace for older kernels), but since they have been in development, I haven’t seen documentation outside of lkml, so you’ll need to figure it out. (On this kernel range, you might find more documentation for tracing these with bcc/eBPF, including using the trace.py tool.)

6.6. Dynamic Tracing

For kernel analysis, I’m using CONFIG_KPROBES=y and CONFIG_KPROBE_EVENTS=y, to enable kernel dynamic tracing, and CONFIG_FRAME_POINTER=y, for frame pointer-based kernel stacks. For user-level analysis, CONFIG_UPROBES=y and CONFIG_UPROBE_EVENTS=y, for user-level dynamic tracing.

Kernel: tcp_sendmsg()

This example shows instrumenting the kernel tcp_sendmsg() function on the Linux 3.9.3 kernel:

# <b>perf probe --add tcp_sendmsg</b> Failed to find path of kernel module. Added new event: probe:tcp_sendmsg (on tcp_sendmsg) You can now use it in all perf tools, such as: perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -aR sleep 1

This adds a new tracepoint event. It suggests using the -R option, to collect raw sample records, which is already the default for tracepoints. Tracing this event for 5 seconds, recording stack traces:

# <b>perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -a -g -- sleep 5</b> [ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ] [ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.228 MB perf.data (~9974 samples) ]

And the report:

# <b>perf report --stdio</b>

# ========

# captured on: Fri Jan 31 20:10:14 2014

# hostname : pgbackup

# os release : 3.9.3-ubuntu-12-opt

# perf version : 3.9.3

# arch : x86_64

# nrcpus online : 8

# nrcpus avail : 8

# cpudesc : Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2670 0 @ 2.60GHz

# cpuid : GenuineIntel,6,45,7

# total memory : 8179104 kB

# cmdline : /lib/modules/3.9.3/build/tools/perf/perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -a -g -- sleep 5

# event : name = probe:tcp_sendmsg, type = 2, config = 0x3b2, config1 = 0x0, config2 = 0x0, ...

# HEADER_CPU_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# HEADER_NUMA_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# pmu mappings: software = 1, tracepoint = 2, breakpoint = 5

# ========

#

# Samples: 12 of event 'probe:tcp_sendmsg'

# Event count (approx.): 12

#

# Overhead Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ....... ................. ...............

#

100.00% sshd [kernel.kallsyms] [k] tcp_sendmsg

|

--- tcp_sendmsg

sock_aio_write

do_sync_write

vfs_write

sys_write

system_call_fastpath

__write_nocancel

|

|--8.33%-- 0x50f00000001b810

--91.67%-- [...]

This shows the path from the write() system call to tcp_sendmsg().

You can delete these dynamic tracepoints if you want after use, using perf probe --del.

Kernel: tcp_sendmsg() with size

If your kernel has debuginfo (CONFIG_DEBUG_INFO=y), you can fish out kernel variables from functions. This is a simple example of examining a size_t (integer), on Linux 3.13.1.

Listing variables available for tcp_sendmsg():

# <b>perf probe -V tcp_sendmsg</b>

Available variables at tcp_sendmsg

@<tcp_sendmsg+0>

size_t size

struct kiocb* iocb

struct msghdr* msg

struct sock* sk

Creating a probe for tcp_sendmsg() with the “size” variable:

# <b>perf probe --add 'tcp_sendmsg size'</b> Added new event: probe:tcp_sendmsg (on tcp_sendmsg with size) You can now use it in all perf tools, such as: perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -aR sleep 1

Tracing this probe:

# <b>perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -a</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.052 MB perf.data (~2252 samples) ]

# <b>perf script</b>

# ========

# captured on: Fri Jan 31 23:49:55 2014

# hostname : dev1

# os release : 3.13.1-ubuntu-12-opt

# perf version : 3.13.1

# arch : x86_64

# nrcpus online : 2

# nrcpus avail : 2

# cpudesc : Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5645 @ 2.40GHz

# cpuid : GenuineIntel,6,44,2

# total memory : 1796024 kB

# cmdline : /usr/bin/perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -a

# event : name = probe:tcp_sendmsg, type = 2, config = 0x1dd, config1 = 0x0, config2 = ...

# HEADER_CPU_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# HEADER_NUMA_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# pmu mappings: software = 1, tracepoint = 2, breakpoint = 5

# ========

#

sshd 1301 [001] 502.424719: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=b0

sshd 1301 [001] 502.424814: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=40

sshd 2371 [000] 502.952590: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=27

sshd 2372 [000] 503.025023: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=3c0

sshd 2372 [001] 503.203776: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=98

sshd 2372 [001] 503.281312: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=2d0

sshd 2372 [001] 503.461358: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=30

sshd 2372 [001] 503.670239: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=40

sshd 2372 [001] 503.742565: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=140

sshd 2372 [001] 503.822005: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=20

sshd 2371 [000] 504.118728: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=30

sshd 2371 [000] 504.192575: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81505d80) size=70

[...]

The size is shown as hexadecimal.

Kernel: tcp_sendmsg() line number and local variable

With debuginfo, perf_events can create tracepoints for lines within kernel functions. Listing available line probes for tcp_sendmsg():

# <b>perf probe -L tcp_sendmsg</b>

<tcp_sendmsg@/mnt/src/linux-3.14.5/net/ipv4/tcp.c:0>

0 int tcp_sendmsg(struct kiocb *iocb, struct sock *sk, struct msghdr *msg,

size_t size)

2 {

struct iovec *iov;

struct tcp_sock *tp = tcp_sk(sk);

struct sk_buff *skb;

6 int iovlen, flags, err, copied = 0;

7 int mss_now = 0, size_goal, copied_syn = 0, offset = 0;

bool sg;

long timeo;

[...]

79 while (seglen > 0) {

int copy = 0;

81 int max = size_goal;

skb = tcp_write_queue_tail(sk);

84 if (tcp_send_head(sk)) {

85 if (skb->ip_summed == CHECKSUM_NONE)

max = mss_now;

87 copy = max - skb->len;

}

90 if (copy <= 0) {

new_segment:

[...]

This is Linux 3.14.5; your kernel version may look different. Lets check what variables are available on line 81:

# <b>perf probe -V tcp_sendmsg:81</b>

Available variables at tcp_sendmsg:81

@<tcp_sendmsg+537>

bool sg

int copied

int copied_syn

int flags

int mss_now

int offset

int size_goal

long int timeo

size_t seglen

struct iovec* iov

struct sock* sk

unsigned char* from

Now lets trace line 81, with the seglen variable that is checked in the loop:

# <b>perf probe --add 'tcp_sendmsg:81 seglen'</b>

Added new event:

probe:tcp_sendmsg (on tcp_sendmsg:81 with seglen)

You can now use it in all perf tools, such as:

perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -aR sleep 1

# <b>perf record -e probe:tcp_sendmsg -a</b>

^C[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.188 MB perf.data (~8200 samples) ]

# <b>perf script</b>

sshd 4652 [001] 2082360.931086: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81642ca9) seglen=0x80

app_plugin.pl 2400 [001] 2082360.970489: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81642ca9) seglen=0x20

postgres 2422 [000] 2082360.970703: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81642ca9) seglen=0x52

app_plugin.pl 2400 [000] 2082360.970890: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81642ca9) seglen=0x7b

postgres 2422 [001] 2082360.971099: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81642ca9) seglen=0xb

app_plugin.pl 2400 [000] 2082360.971140: probe:tcp_sendmsg: (ffffffff81642ca9) seglen=0x55

[...]

This is pretty amazing. Remember that you can also include in-kernel filtering using –filter, to match only the data you want.

User: malloc()

While this is an interesting example, I want to say right off the bat that malloc() calls are very frequent, so you will need to consider the overheads of tracing calls like this.

Adding a libc malloc() probe:

# <b>perf probe -x /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.15.so --add malloc</b> Added new event: probe_libc:malloc (on 0x82f20) You can now use it in all perf tools, such as: perf record -e probe_libc:malloc -aR sleep 1

Tracing it system-wide: